Review – Shadowrun (Genesis)

Beginning as a pen-and-paper RPG in 1989, Shadowrun was followed by a strange scattershot of games based on the license in the early ’90s. Its bizarre and tantalizing mix of fantasy magic and cyberpunk technology graced three (or, like, two and a half) consoles in the ’90s: the SNES in 1993, the Genesis in 1994, and the Sega CD in 1996 (in Japan only). That would be typical if they were all ports of the same game, but they were, in fact, completely unrelated projects by different developers with their own approach to the material. I’ve already covered the SNES version, developed by Beam Software, which was a fairly linear mix of adventure and action RPG. The Genesis version developed by BlueSky Software, perhaps better known for Vectorman and the Genesis Jurassic Park titles, is a completely different beast that pays closer respect to the tabletop from which it came from.

Shadowrun on the Genesis has been taunting me for some time now. I’ve picked it up in earnest twice before and burned out long before seeing the credits. We’ll get to the reason why I struggled to bring completion, but despite my inability to cap off my adventure with it, it stuck in my consciousness to the point where, when I thought about the Genesis console, Shadowrun would instantly spring to mind. I’ve been diving back into the universe through a recent playthrough of the SNES version and more time devoted to the novels associated to the license, so it seems like my best chance to finally put it away.

I’m probably not touching the Sega CD version. My Japanese isn’t that good.

BACK TO THE SHADOWS OF SEATTLE

It’s Seattle, 2058. You’re placed in the shoes of Joshua, a novice shadowrunner who is beating the streets, trying to find the people responsible for killing his brother. Because revenge is the only dish available in the cyberpunk future, and it’s best served… all the time. Shop owners could probably set their watches to the people busting through their doors inquiring about who killed them, their family members, or their dogs. The local waterparks are struggling because no one can find time for recreation between all the revenge they’re seeking. Okay, I’m done.

So it’s not the most unique plot. Nor is it a particularly compelling one. In fact, it isn’t even a very good plot. But that’s Shadowrun in a nutshell. Everything is so much bigger than the individuals that the plots follow, that they’ve only got a limited amount of agency with which to interact with the world. Narratives are all but forced to be personal, and there are no greater personal stakes than revenge. Case in point; the recent Harebrain Schemes trilogy of entries in the series, games that I consider to have actually capable narratives, are all, more or less, about revenge.

But this was 1994, that particular dead horse hadn’t yet turned to mulch, and plot in video games still wasn’t exactly a priority. It does what it needs to do; aside from your familiar roots, you’re a blank slate protagonist with no connections within Seattle. It’s up to you to establish yourself, build your character, and fill up your address book. At least you don’t have a case of amnesia.

CUT THE DREK, OMAE

On the SNES, Shadowrun took a lot of liberties with the source material in an effort to make it more accessible and straightforward. Names of major characters and organizations had been changed, progression had been simplified, and the locations had been made abstract. The Genesis version adheres much more strictly to the pen-and-paper standards.

While the SNES version was a fairly narrative-focused ordeal, the Genesis option offers up a more open experience. The narrative doesn’t lead you by the hand, and you’re capable of ignoring it for large stretches of time as you focus on your character. If you don’t feel like following up on a lead right away, you can focus on the unlimited number of sidequests provided to you by the game’s numerous “Mr. Johnsons.” These range from simply escorting someone across town to infiltrating a megacorporation in search of a defecting employee or package. These runs provide you with money (nuyen) and experience in the form of Karma, which you then spend on any number of skills and attributes. Money can be used to upgrade your equipment or purchase information on contacts from the more tight-lipped of your associates.

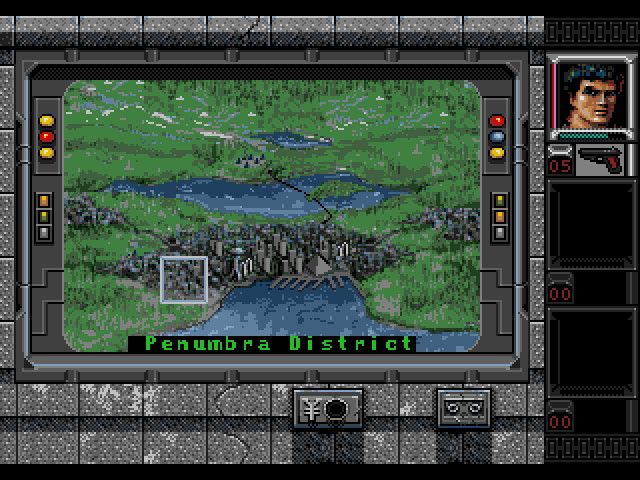

To that end, there’s a lot of freedom available. Whether you focus on immediately building yourself into a tank, upgrading your decking gear, pursuing the story, or hiring a team, there’s always something to do. Seattle is a big place, covering several different sections of the city from the Redmond Barrens, to the neighbouring lands of Salish-Shidhe, all of which are open from the beginning and each of which contains their own sights and sounds. It can be overwhelming at first, confusing even, but with a bit of time, it should start feeling like home.

DUMPSHOCK

Through running the shadows, you’ll inevitably bump into the game’s biggest issue; it’s massively unbalanced. Worse than that, it’s unbalanced in layers. Like a cake that you tried to stack before actually baking.

A lot of this centers around a poor progression when it comes to the sidequests. When you start out, you only have one Mr. Johnson (anonymous buffers that provide contracts on behalf of their clients) that you can visit, Gunderson, who gives you small jobs within the Redmond Barrens that mostly pay like crap. Unfortunately, from there it’s difficult to start making money and karma reliably. The next nearest Johnson either gives money that barely constitutes a pay raise over Gunderson, or missions that are too difficult to complete reliably with the low skill level you’re likely to have when you need the money. The result is that you’ll likely wind up just grinding Gunderson until you have the skills and equipment to take on a better Johnson’s missions, and at that point you’re probably better of just skipping to the highest paying one, Caleb Brightmore, since the high-level missions don’t differ very substantially in difficulty from the mid-level ones.

You choose from three character classes: samurai, decker, and shaman, and they too are not very balanced. It’s easy enough to build up a shaman or samurai, their points are very focused and their equipment is relatively limited. The decker, on the other hand, is pretty stupid. It’s the easiest profession to make money in, but the hardest profession to actually get into. If you jack into the matrix with inadequate gear, you’re going to get booted out at best, and at worst, you’re going to get your equipment destroyed. You then have to spend hard-earned money on repairs and upgrades.

Better equipment is ridiculously expensive. To get a decent deck to handle even the moderate missions, it costs tens of thousands of nuyen, which, as we’ve previously covered, is hard enough to come by. This makes decking an almost end-game skillset, when it’s something that you’re given the option of specifying in from the beginning. Once you’ve been built up, however, making money becomes a breeze. Unfortunately, at that point, you’ve already been spending your money on the most expensive stuff in the game and there isn’t much use in accumulating more.

TRY NOT TO SLOT THIS UP

That, in few words, is what caused me to grow tired of the game and put it aside two times prior. My mistake was attempting to focus entirely on my character, a play style that the game is hostile towards when approached by a new set of eyes. This lap around, I spent more time exploring the narrative, taking breaks to grind for more currency. It still felt like something of a slog, but I eventually got through.

What I found through doing that was that the freedom that Shadowrun offers is pervasive everywhere. The narrative essentially hands you a number of leads and leaves it to you to follow them. Track down someone who might know something about what happened to your brother’s team, run favours for someone, break into a corporation to find out what they know; it’s very non-linear and admirably organic. At times, the information given can seem inadequate, but unlike the SNES version, I never needed to consult a guide to get through it. To that end, it has my respect.

OUT OF THE SHADOWS

It’s a largely imperfect game. Narratively, it’s weak, but structurally, it’s ambitious. Its character progression is an uneven slog, but the freedom given is refreshing. The combat is lacking, but the variety is fun. It annoys me in many ways, but I can’t get it out of my head. In that way, it’s a lot like the SNES version.

There’s a lot of debate about which version of Shadowrun is the superior one. Hardcore RPG aficionados and lovers of the tabletop game tend to side with the Genesis version. It’s easy to see why. It’s a much more loving take on the property, diving headfirst into everything that makes Shadowrun unique.

That doesn’t make up for how uneven it is. Even with my established affection to the nerd-tacular mashup of Tolkien-esque fantasy and Bladerunner-esque cyberpunk, it took a lot of effort to reach the end. A lot more polish and more care would have gone a long way in making the game a more engrossing and enjoyable experience. Instead, it’s weighed down by grind and colossally unbalanced. As it stands, Shadowrun on Genesis is a game I recommend, but not everything I want it to be.

6/10

This review was conducted on a second model Genesis (revision VA3 for you hardware nerds) using an authentic copy of the game.